The chances are that you may have found this website after doing an internet search for ‘Titanic’s centre propeller’ or similar. It’s quite odd that such a mundane subject should generate such interest, nonetheless it is often the subject of passionate discussion online (or, all too often, unnecessary and vitriolic argument).

Titanic and her sisters were propelled by a ‘combination’ system which involved two triple-expansion reciprocating steam engines driving her port and starboard propellers. They were triple-screw steamers in that they had a smaller, centre propeller which was driven by a low-pressure Parsons steam turbine. The benefit of this system, combining old and new technology, was that the steam turbine used low-pressure steam exhausted from the reciprocating engines which would otherwise have been wasted. The turbine itself generated about one-third of the total power output of the propelling machinery.

For decades, Titanic was depicted in books, movies, and television programmes with three-bladed port and starboard propellers and a four-bladed centre propeller. This configuration became accepted as fact However, there is no evidence to support it: in reality, it was mere assumption.

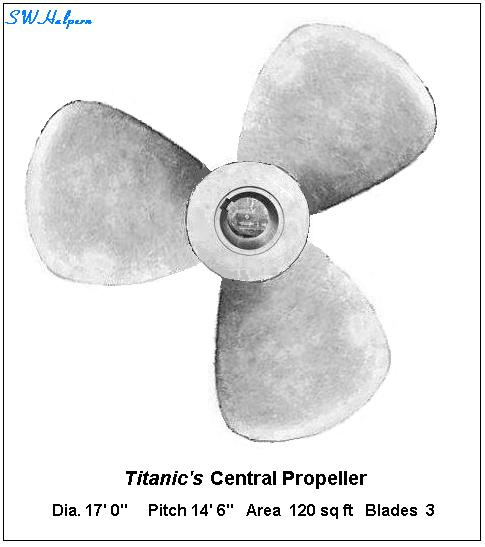

The evidence we have – directly from the shipbuilder Harland & Wolff’s own records which documented Titanic‘s propeller configuration as completed – is that she had a slightly larger, three-bladed centre propeller. (There were modifications to the port and starboard propeller specifications as well, which are often overlooked.) Unfortunately, this evidence did not come to light until 2007, when Mark Chirnside was researching at the Public Record Office Northern Ireland (PRONI) supported by a local researcher, Jennifer Irwin. However, since that time, additional material has been discovered which supports it.

All of this evidence and accompanying commentary can be found in a dossier here. It includes links to articles with the primary source material, as well as contextual information and comment from renowned Titanic experts such as Samuel Halpern, Ken Marschall and Bill Sauder. There is also a Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) feature.

Familiarity Bias

Our interpretation of history is not static. What happened in the past remains the same, but historians’ understanding of historical events is constantly being tested or updated by the discovery of new material. Revising our understanding of the past is a continual process and the bread and butter of competent historical research. However, as humans we all have a natural bias towards the familiar. That bias shows up when many people happily accept a long-held assumption as if it were fact, but reject primary source evidence for no valid reason.

What we see today is often heated discussion or debate as to whether Titanic had a three-bladed or four-bladed centre propeller. However, as far as the available evidence is concerned, it is not a debate.

The correct approach for historians to take is to come to an understanding and interpretation of the available evidence, recognising that this interpretation (like all others) may need to be subject to revision in future.

The Importance of Using Primary Sources: A Case Study

One of the most fundamental problems in reaching an accurate understanding of Titanic‘s history today is the vast array of secondary sources (such as books, articles or television programmes) which simply repeat claims or assumptions that are not based on primary source documentation (such as contemporary, original documentation in Harland & Wolff’s records). The majority of technical statistics concerning her propeller configuration are simply those of Olympic at the time of her maiden voyage in 1911, which are (even today) published as if they were accurate for Titanic. We see this years after the primary source evidence to the contrary came to light. There is a widespread failure to utilise primary sources and all too much Titanic literature contributes little new to the subject.

A good example of misinformation is the publication of many photos of Olympic‘s propellers which are routinely captioned or passed off as Titanic. One of the most popular of these, used in many exhibitions, is a stunning photo of Harland & Wolff shipyard workers staring up in awe at the ship’s stern towering above them and the enormous propellers. Unfortunately, not only is it an Olympic photo, but it dates to January 1924 – twelve years after the Titanic disaster. The consequence of all this is that there is a widespread lack of understanding that there are no known photos of Titanic in dry dock with her propellers fitted (installation took place in February 1912). Naturally, this causes a lot of confusion, because the majority of people interested in the subject will obtain their information from secondary sources.

The subject of Titanic‘s propeller configuration is therefore a very good case study in the importance of using primary sources. It is an example where the primary source evidence is directly at odds with the most common claims in secondary sources.

Contact

To get in touch, please follow the links to Mark Chirnside’s Reception Room . There is a contact form, as well as an Updates page where you can sign up for regular emails when new articles are published on that site.